You can change negative thinking by learning to recognize and correct patterns of unrealistic thoughts. Clinicians call these patterns “cognitive distortions.” Common cognitive distortions include all-or-nothing thinking, thinking you know other people’s thoughts (“I’m sure she hates me!”), and predicting the future (“I’m never going to get better at math.”).

How to Change Negative Thinking Patterns

How to Change Negative Thinking Patterns

Recognizing unhealthy thinking errors called 'cognitive distortions'

Clinical Expert: Jeff DeRoche, LCSW

en EspañolWhat You'll Learn

- How can negative thinking patterns affect kids’ lives?

- What are some of the most common negative thinking patterns?

- How can parents help kids change negative thinking patterns?

Quick Read

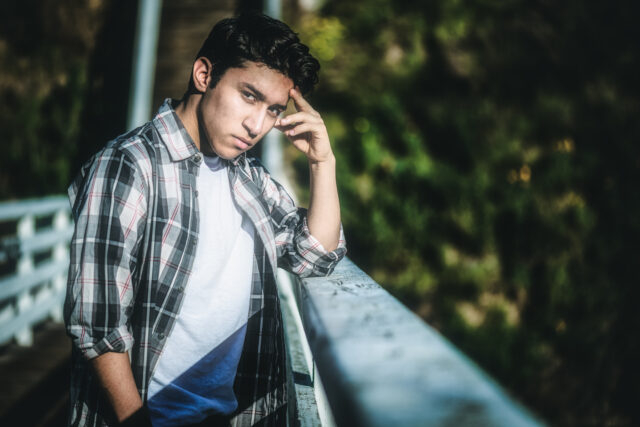

Kids can be hard on themselves — especially kids with mental health challenges. They can get stuck in negative thinking patterns that may make depression, anxiety and upsetting feelings even worse.

Repeated patterns of unrealistic negative thinking are called cognitive distortions. Cognitive distortions are basically thinking mistakes. Learning how to recognize cognitive distortions can make it easier for kids to think more positively and feel better about themselves.

Mental health experts have identified several common cognitive distortions. One is all-or-nothing thinking, where kids think that one bad thing means that everything is bad. For instance, a child might think that if they don’t get perfect grades, they’re a terrible student.

Several common cognitive distortions have to do with believing you know things that are impossible to know. For example, a child might think they know others’ thoughts (“I’m sure they think I’m stupid!”) or what will happen in the future (“I’m never going to get better at math.”). They may also focus on bad things (like one kid being mean) instead of good ones (like lots of other kids being nice).

It’s also common for kids to view things as proof that there’s something wrong with them. They might think they caused things that they didn’t: “My parents are getting divorced because I cause too much trouble.”

Learning about cognitive distortions and talking about them with your kids can help them think more positively. You can practice noticing negative thinking together. The goal is for kids to understand that we all make thinking mistakes sometimes and learn how to correct them.

If you notice that your child makes a lot of cognitive distortions and gets very emotional about them, getting support from a mental health professional can also help.

Full Article

10 min read

Children can be their own worst critics. This is particularly true for kids with mental health disorders, who may be especially down on themselves. They can get stuck in negative thinking patterns that contribute to depression, amp up their anxiety, or make painful emotions feel overwhelming.

If your daughter wasn’t invited to a birthday party, for example, she may decide that everyone who went to the party hates her. If she forgets a line in a school play, she may insist that she ruined the whole performance.

These negative thinking patterns are often unrealistic, but they can have significant impacts on our emotions, behaviors, and world views. Mental health experts call them cognitive distortions — they’re also sometimes referred to as cognitive errors, thinking mistakes, or thinking errors.

“Some amount of cognitive distortion is normal,” says Jeff DeRoche, LCSW, a clinical social worker. “We all make thinking mistakes. It’s when that kind of thinking is chronic and entrenched that the thoughts are likely doing a number on a child’s emotional life. I’ve never seen someone suffering under the weight of any kind of behavioral health problem who isn’t making cognitive errors quite regularly.”

In cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), kids are taught to recognize common cognitive distortions that may be making them feel bad. But whether or not your child is in therapy, it can help to recognize and identify them when you see them. Here they are distilled into 11 common categories. DeRoche emphasizes that there’s a lot of overlap among them.

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking (also referred to as Black-and-White Thinking or Dichotomous Thinking)

What it is: Seeing things in only two categories, so they’re either good or bad, black or white, with no shades of grey. A common distortion that makes you think — and therefore feel — that if something is not all of what you want then it’s none of what you want. It’s also thinking that you have to perform well on everything — perfectionism — or you’ve totally failed.

For example: I didn’t get into my first choice school so my hopes for high school are totally dashed. Or: If I didn’t get that A+ then I’m a failure.

2. Emotional Reasoning

What it is: Believing that because you feel something it must be true, even when there’s no evidence other than the feeling.

For example: I feel lonely, therefore no one likes me. Or: I feel afraid to go in an elevator, therefore elevators are dangerous places.

3. Overgeneralization

What it is: Taking one negative event or detail about a situation and making it a universal pattern that is a truth about your whole life.

For example: This person didn’t want to hang out with me. No one ever wants to hang out with me! Or: I messed up my chemistry experiment today. I never do anything right!

4. Labeling

What it is: Putting a negative label on yourself – or someone else – so that you no longer see the person behind the label. When you lock someone in place like that, your understanding becomes so rigid that there’s no wiggle room to see yourself or another person differently.

For example: I fell down trying to score that goal in soccer today. I’m a horrible klutz. I didn’t have anything to say in that conversation. I’m totally uninteresting!

5. Fortune-Telling

What it is: Predicting something is going to turn out in a negative way. This can become a pessimistic way of viewing the future, and it can impact your behavior, making the event you’re fortune-telling more likely to turn out badly.

For example: I know that I’m going to do horribly on that test (so you panic and perform less effectively on it). Or: If I reach out to this person, they’re not going to want to talk to me or accept me (so you don’t reach out and take a chance on connecting with someone you want to know better or get help from).

6. Mind Reading

What it is: Assuming that you know and understand what another person is thinking, and typically being sure it reflects poorly on you.

For example: I’m talking, and the person I’m talking to doesn’t seem to be paying attention. I’m sure they don’t like me. (In fact it might be that they’re just distracted, or stressed about something unrelated to you and are having a hard time focusing.)

7. Catastrophizing

(also called Magnification)

What it is: Taking a problem or something negative and blowing it up out of proportion.

For example: This party is going to be the worst experience ever! Or: If I don’t get a base hit I’ll die of embarrassment.

8.Discounting the Positive

(also called Minimizing)

What it is: Taking something positive that happened and minimizing it so that it doesn’t “count” as a good thing in your life or experience. It discounts any evidence against our negative view of ourselves or our situation.

For example: I did well on that one quiz, but I just got lucky. Or: This person said, ‘I love hanging out with you,’ but she’s just being nice. She doesn’t really mean it.

9. Mental Filter (also called Selective Abstraction)

What it is: Seeing only the negative instead of looking at all the positive or neutral aspects of an experience.

For example: You write a paper for a teacher and they give you plenty of positive feedback on it, but you spelled someone’s name wrong. All you can think about is the misspelling. Or you have many positive conversations in a day, and one in which you say something embarrassing. You focus with total horror only on the embarrassing statement you made, forgetting all your other social interactions.

10. Personalization

What it is: Making things about you when they are not. This includes blaming yourself for what is beyond your control and also taking things personally when they are not intended to be harmful to you.

For example: If I hadn’t demanded so much of my parents, maybe they wouldn’t be getting a divorce. Or: How dare that person walk in front of me – that was so disrespectful! (When the person just didn’t notice you and cutting you off was an honest mistake.)

11. Imperatives

What it is: Thinking in “shoulds” and “musts” (and the inverse, “should nots” and must nots”).

For example: I should be able to give presentations in class without feeling any anxiety. What’s wrong with me? (Of course, thinking this way, on top of feeling nervous, makes you even more nervous about speaking!)

How parents can help kids

CBT helps kids identify, challenge, and ultimately restructure their thinking so that they can live healthier, better adjusted lives. Taking a cue from CBT, parents, too, can help kids recognize cognitive distortions, and reduce their intensity.

The best way to start is with your own cognitive distortions, says DeRoche. Once you’ve learned the different types, try recognizing them in your own patterns of thought. For example, if your child has anxiety, you might personalize this, assuming it’s your fault, and then label yourself a “terrible parent.”

“I can’t stress enough how important it is to notice cognitive distortions in a way that’s not judgmental,” says DeRoche. “When you get skillful at noticing distortions in your own thinking, you are in a much better place to help someone else notice theirs. And be humble about noticing your own – call them out in a playful way when you make them, and let your kids call yours out, too.”

The goal is to model for your children that we all make thinking mistakes, he adds, and “the act of noticing them and making corrections with levity and self-compassion is usually the best medicine.”

To learn the cognitive distortions, you can help your children make flash cards so you can quiz each other. The Internet is full of colorful posters of the various distortions as well, and CBT phone apps often ask the user to label the distortions in their thinking from menus of choices.

“Keep this work together light,” DeRoche advises. “Even very experienced therapists have to work hard to safeguard against inadvertently invalidating children by telling them their thinking is ‘in error’ or ‘illogical.’ Even when it is, we can’t assume they are always going to be ready or willing to see it that way. Sometimes we get stuck on how we feel and it’s tough to rationally evaluate how we’re thinking.”

Most importantly, if your child is making many cognitive distortions – if their thinking is very rigid, their expectations are chronically negative, or their feelings are too strong for them to be reflective about their thinking mistakes, it’s time to ask for help from experts. It’s great to collaborate with your child in learning and identifying cognitive distortions – especially as a supplement to good therapy – but a child who is seriously struggling may need treatment from a mental health professional.

Frequently Asked Questions

This article was last reviewed or updated on October 30, 2023.

Topics

Juliann Garey

Juliann Garey is a journalist and novelist and educator. As a clinical assistant professor at the NYU Langone School of … Read Bio

Was this article helpful?

Related Reading

-

How to Help Kids Who Are Too Hard on Themselves

Bolstering self-critical children who tend to talk themselves down

How to Help Kids Who Are Too Hard on Themselves

Bolstering self-critical children who tend to talk themselves down

-

Behavioral Treatments at a Glance

An overview of behavioral treatments, how they work, and how they can help

Behavioral Treatments at a Glance

An overview of behavioral treatments, how they work, and how they can help

-

Behavioral Treatment for Kids With Anxiety

Kids learn to handle the bully in the brain

Behavioral Treatment for Kids With Anxiety

Kids learn to handle the bully in the brain

-

Metacognition: How Thinking About Thinking Can Help Kids

A powerful skill for building resilience

Metacognition: How Thinking About Thinking Can Help Kids

A powerful skill for building resilience

-

Complete Guide to Managing Behavior Problems

When children struggle with their behavior, it can have a negative impact on everyone in…

Complete Guide to Managing Behavior Problems

When children struggle with their behavior, it can have a negative impact on everyone in…

-

Helping Kids With Flexible Thinking

How flexible thinking can help children handle uncertainty and change

Helping Kids With Flexible Thinking

How flexible thinking can help children handle uncertainty and change

-

What Is Motivational Interviewing?

A deep dive into a form of therapy that helps teens change unhealthy behaviors

What Is Motivational Interviewing?

A deep dive into a form of therapy that helps teens change unhealthy behaviors

More Related